1.Chiming the Universal

A while back, I spent a wonderful morning facilitating my workshop Expanding Our Frame with junior students at Pratt's design school. We explored design through three different lenses:

For Self

For Instagram (or the presentation of self)

For Community

Each of these frames has a remarkably different tenor. It's easy to champion designing for community—addressing real needs, fostering belonging, creating systemic change—and to critique designing for social media, with its hollow images and leanings toward comparison and conformity. But the most misunderstood lens, especially for young creatives, is designing for self.

Often, designing for oneself gets collapsed into designing for something like Instagram. But these two frames couldn't be more different.

Designing for self requires an internal stillness and a quiet so that you can hear your own curiosities and desires. It often leads to a flow state where you can paradoxically lose yourself and your sense of time. In this state, you make a mark on the page and play, following your intuitive feedback once you see the results. No, you might think, not that, that's not it. Or yes, that's more like it, but I wonder, what if...

It's true what Rick Rubin says: "the audience comes last."

Well, isn't this bad? you might ask. Isn't this wrong? Shouldn't we be designing for other people? Shouldn't we be empathetic and of service? Isn't this the height of self-indulgence?

To which my response is a loud and resounding NO!

Self-expression, made first and foremost for oneself, is an act of courageous generosity.

Why? Because when we have the courage to be honest and particular about who we are inside our art and design practices, something mysterious and expansive unfolds. Your art may even chime something universal inside the larger human experience. Your design practice will move and inspire people. Your artwork will make people feel seen.

Here's my little speech from the workshop:

As in all of the arts, one of the incredibly magical things about design is that if you develop a personal sensibility that is deeply and authentically your own—one that is a courageous expression of your own curiosities—well, this is often what will go on to resonate with the universal.

Developing your own design sensibility is a worthy use of one's life.

Especially as so often, the personal becomes the universal.

2. Expanding Our Frame - The Workshop

Designing for community requires being human-centered, which requires being deeply curious, which requires truly listening to people.

One of the tremendous benefits of having a practice that is an expression of self is that we become more aware of ourselves. Such a practice draws a clear container around our personal concerns and assumptions, supporting us in not subconsciously projecting them onto other people.

We stop orienting ourselves as an authority "doing good" for others.

After all, very few people appreciate someone (let alone an institution) insisting that "this is for your own good." It has the putrid air of disdain and judgment: "What? I'm just trying to help."

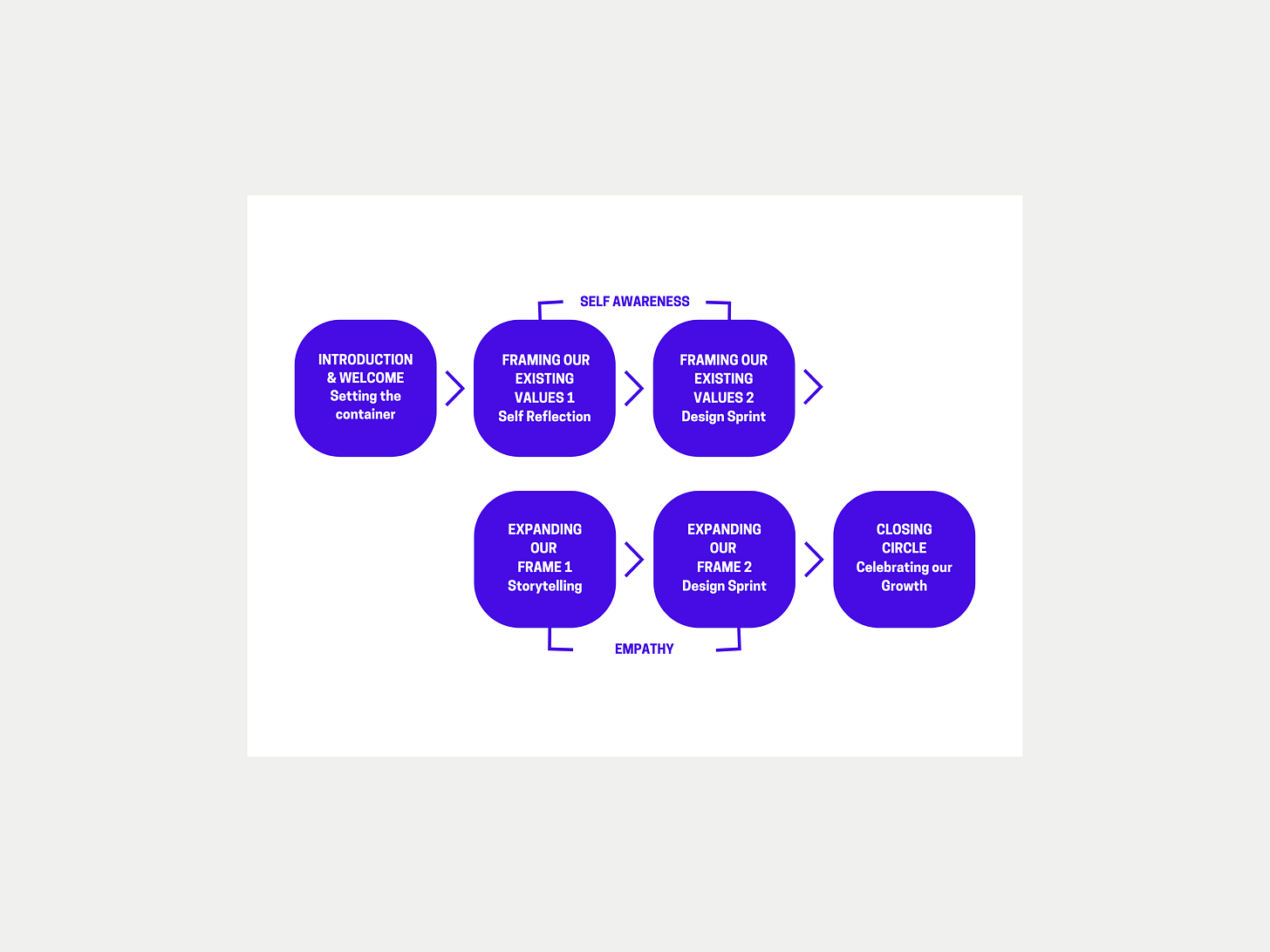

For this reason, in the Expanding Our Frame workshop, we spend the first half developing self-awareness around our personal design sensibilities—celebrating it! The second half can then focus on cultivating deep listening and empathy for other people, “expanding our frame”, and designing from this new orientation.

First Half: Self-Awareness

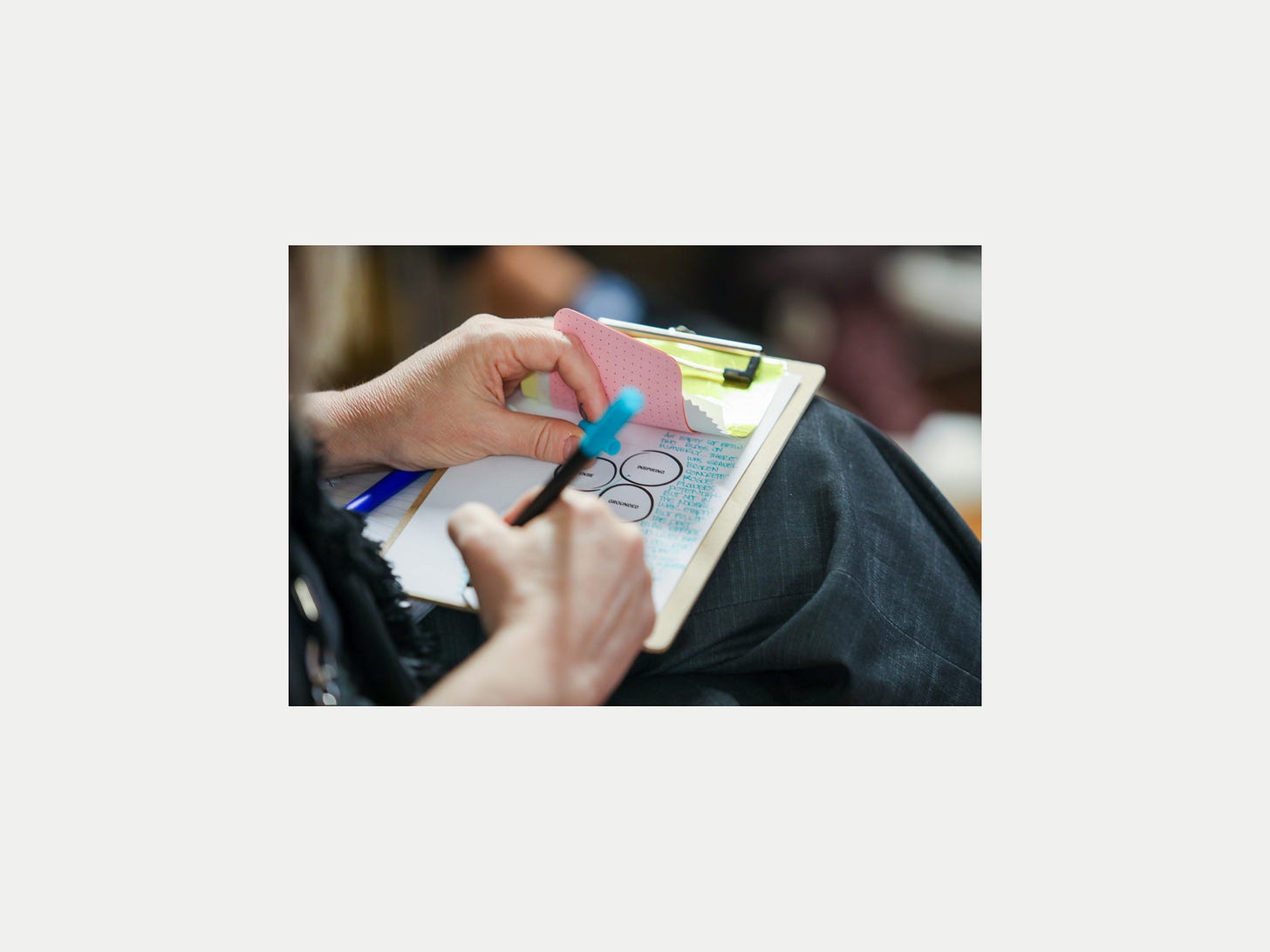

I lead students through a reflective exercise that explores their early spatial experiences and helps deepen their personal design values.

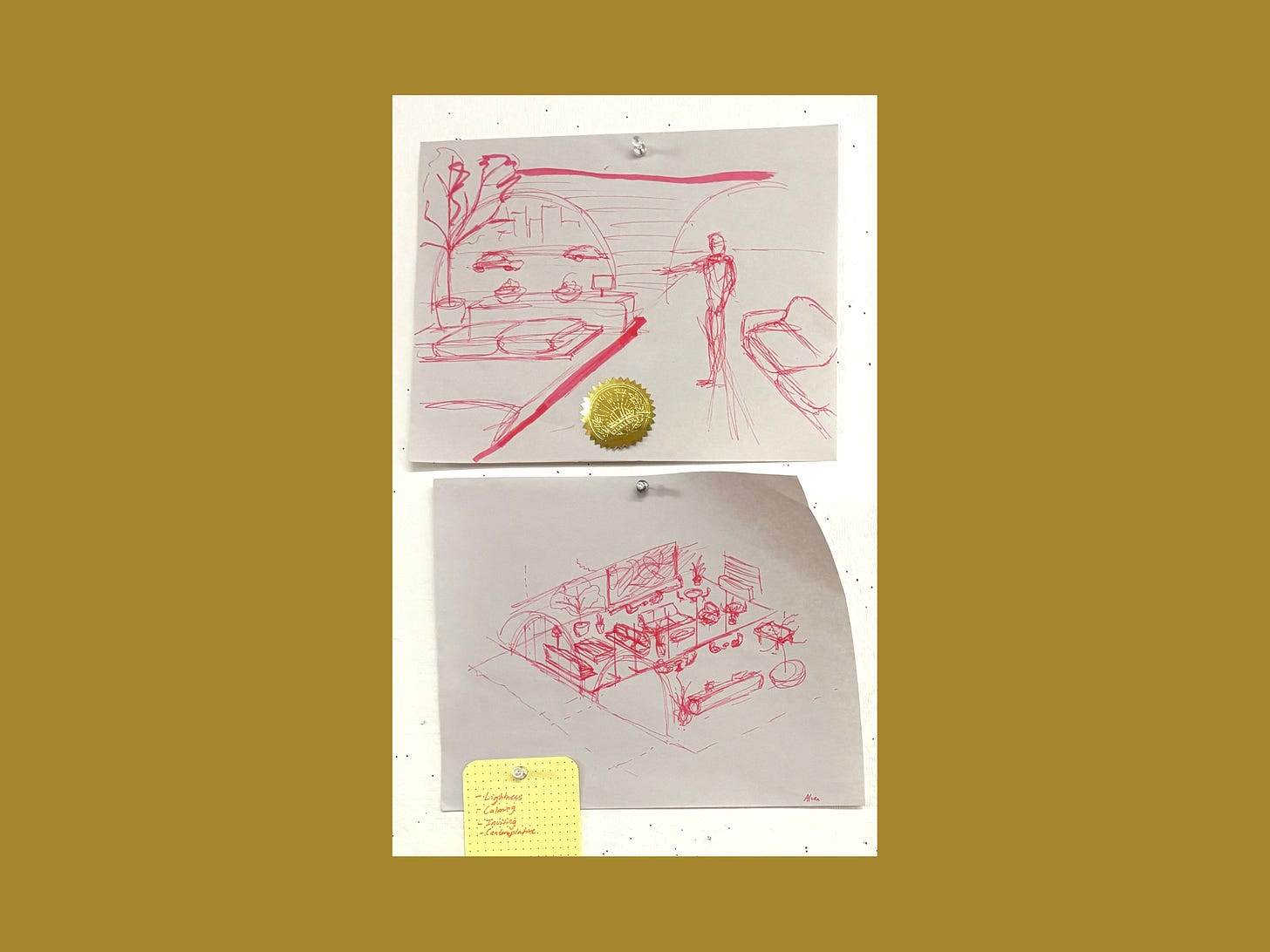

Next, we enter a design sprint where students design the entrance and lobby to a hostel. Students are encouraged to have fun and work to realize some of the ideas and values they've distinguished in the reflective exercise.

The results are joyous.

One young designer was passionate about the sky, having uncovered a happy early memory where as a child she regularly lay in long grass watching the clouds shift above her with her siblings. She designed an aperture window that brought the sky inwards. Others were deeply curious about transitions, gathering spaces, gardens, light, or materiality. Everybody followed their hearts.

Second Half: Empathy

For the second half of the workshop, students had the same design brief but this time it was explicitly for a low-cost hostel—perhaps one that people could stay in after they had been detained by the criminal legal system.

Jean Michele, a former graduate of Young New Yorkers (an arts-based Alternative-To-Incarceration program) came to share his lived experience and deep wisdom.

How students listen in this moment is critical.

We practice the art of listening without adding—akin to meditation but where you listen deeply to another person and simultaneously bring awareness to your own thoughts and biases reacting to what's being said. Then, and this is the critical part, instead of allowing your own thoughts to dialogue with the speaker (or to reconfigure what's being said into the inner archive of what you already know), you let your thoughts pass. Then you return your attention back to your listening, just as you would return your presence back to your breath in meditation.

Jean Michele shared his experiences, including that he was forced to sleep on a layer of grime in central bookings, a group cell underneath the Kings County criminal court. "There's only one window and it's way up there. You just want to go outside."

When asked by a student what he'd most like from the lobby, he said, "Just an indication that you care. Not having things left broken or dirty. And art." His face lit up. "Art, it makes you lighter inside."

His incredible generosity in sharing his experiences and wisdom allowed us to begin to design in a human-centered way. And so, with a notable surge of energy from the group after Jean Michele's stories, the students entered their second design sprint.

The designs that came back were incredibly heartening. As students shared their ideas they often referenced something Jean Michele had said.

"I was thinking," said one student presenting his design back to Jean Michele, "that what's so great about luxury hotels is the incredible service." I tried not to gasp at the apparent audacity. "And that's exactly what's missing in your experiences. Someone being happy to see you, someone caring about what you might need." The student's design in the first round had been a lush axonometric complete with soaring arches, large art work, designer furniture and sculptural planting. His design now formed a background to his drawing of a person with their arm outstretched to happily greet someone.

"That's great, man," Jean Michele beamed. "Just that. Just one person caring. That would make a huge difference.”

3. Framing Our Existing Values—Worksheets and Facilitation Questions

Hello my magnificent 17 paid subscribers! Kisses on your foreheads.